Delta-8 THC, HHC and many other alternative cannabinoid products have brought intoxicating hemp to gas stations and CBD stores across the country, but regulations are often lacking or virtually non-existent.

The American Trade Association for Cannabis and Hemp (ATACH) has made a series of recommendations as part of a white paper, calling on Congress to step up and rectify this situation through the 2023 Farm Bill. Notably, the paper argues that the definition of “hemp” should be changed to reflect the fact that it isn’t really “rope, not dope” that was legalized back in 2018.

ATACH commented to us that, “at the very least, regulators need to age-limit these products, provide lab testing, review how they are being advertised and sold, and keep intoxicating products within cannabis regulatory programs.”

So, what does the paper say? And how would these recommendations work in practice? You can read the full white paper to get all the details, but here are the main points.

Key Recommendations

The paper proposes several changes at both the state and federal level to address these issues and close the loopholes. These include:

- Revise the definition of hemp to account for the range of products on the market, and ensure that finished products are regulated.

- Add a definition of “work in progress hemp extract” with an increased limit of 1% delta-9 THC for farmers and processors, but not for finished products.

- Establishing the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) as the regulator of intoxicating products, and have non-intoxicating products regulated by the FDA immediately.

- Account for the total intoxicating cannabinoid content of the product through some new approach.

- Normalize testing procedures, train state crime labs to test hemp for enforcement purposes and mandate testing of hemp (including known contaminants) at the state level.

- Fit intoxicating hemp products into existing structures for the sale of intoxicating products (like alcohol) at the state level, or bring them into the regulated cannabis market if the state has one.

- Prohibit sales of intoxicating hemp products to minors and mandate child-resistant packaging.

- Require accurate labeling of hemp products.

While this isn’t an exhaustive list of the recommendations, these are the key points raised by the paper.

ATACH’s White Paper: What It Says and Why

The white paper from ATACH comes in the context of the 2023 Farm Bill, which is set to replace the 2018 bill that created this explosion of hemp products on the market. Broadly, the paper argues that Congress needs to take several steps to protect consumers, differentiate between intoxicating and non-intoxicating products in law and prevent youth from accessing intoxicating products.

Delta-8 THC, delta-10, HHC and a range of other rare-but-intoxicating cannabinoids were created as a result of the 2018 Farm Bill. This bill defined hemp in a way that opened the floodgates for a range of products, sold on the basis that they have less than 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight, which the bill categorizes as hemp. Consumer products flooded the market, with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) retaining authority over hemp products for human consumption, but doing very little in the way of regulation.

The paper describes the core issue, “Critically absent from the Farm Bill is a framework, short of FDA’s involvement, for how finished products intended for human consumption should be regulated. Relying on this regulatory gap, the [hemp synthesized intoxicant] industry emerged shortly after passage of the 2018 Farm Bill, armed with an incomplete definition of hemp that based its legality on only a percentage of delta-9 THC content or the original plant and lacking fundamental finished product safety regulations.”

The bill, in a nutshell, is full of holes. It’s unlikely the authors of the legislation predicted the wealth of products that their words could include, and as a result there was little consideration given to the consequences of the bill. The paper argues that companies’ creation of “hemp synthesized intoxicants” (more on this below) such as delta-8 THC means that dangerous, poorly-understood and intoxicating products are sold without adequate testing and with doses that would often be illegal in adult use cannabis programs.

What Are HSIs?

Hemp-synthesized intoxicants (HSIs) are defined by the paper as:

“An intoxicating cannabinoid which is synthesized from a non-intoxicating constituent found in hemp varieties of the Cannabis sativa L. plant. They are not naturally-created products, but are typically created through a semi-synthetic conversion process.”

The (partial) list of HSIs in Appendix B includes:

- Delta-7 THC

- Delta-8 THC

- Delta-9 THC

- Delta-10 THC

- Delta-6a10a

- HHC

- THCp

- THCv

- THCa

- THC-O acetates

And others such as HHCp or delta-8 THC-O which tend to combine aspects of two novel cannabinoids.

The paper points out that these chemicals are produced from natural hemp components like CBD through chemical processes like isomerization and functionalization. ATACH argues that these production methods are “dangerous and require specialized equipment” and points to heptane as an example of a known toxin used in the production of HSIs. It points out that if producers don’t remove these chemicals, this raises significant concerns.

We asked Chris Lindsey – who answered our questions on behalf of ATACH – about the risks of HSIs, “The known risk with HSI’s comes from the contaminants that can appear in products if they are not removed. Without a regulatory system, there is zero incentive for manufacturers to clean their wholesale products, because (so far) there are no serious repercussions for selling products that get used in consumer goods and put people at risk.”

What the Paper Gets Right

The paper gets a lot of things right and draws attention to some key areas Congress needs to consider carefully when drafting the 2023 Farm Bill.

Redefine Hemp to Account for the Range of Available Products

The 2018 Farm Bill definition of “hemp” is ultimately the reason for all the “HSIs” on the market today. Crucially, the only defining characteristic of hemp is that it’s a cannabis plant with less than 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight. Other than that, it includes all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids and isomers, whether growing or not, that come from the plant.

Armed with only this definition – and correctly, since it is currently the law – producers made all manner of hemp products, likely totally unintended by the original authors. The ATACH paper calls on the federal government to “adopt a revised definition of hemp in the 2023 Farm Bill which accounts for all categories of hemp products, cannabinoids, and importantly, those that are intoxicating and can be synthetically produced.”

ATACH pointed to this as the paper’s most important recommendation, commenting to us that:

“Congress must expand the definition of hemp to acknowledge the broad range of finished products that are currently not regulated. The purpose is to enable a framework that would more clearly allow agencies to move forward with guidelines based on the type of product and its use. The current definition of hemp accounts for production and raw plant material rather than finished products, and Congress’s failure to act on legalization has created a situation in which there is currently a solution for nobody at the federal level – neither non-intoxicating products such as those containing CBD, nor intoxicating products.”

However, the paper doesn’t propose a specific definition or a method of “expanding” the current one which would account for this. We asked ATACH about what this would entail, and whether splitting the definition into something like “industrial hemp” and “intoxicating hemp” would work:

“We were trying to avoid defining intoxication, since that is extremely problematic. Is intoxication when a cannabinoid serves as a sufficiently potent agonist for the CB-1 receptor? Or more like impairment found in DUI law? Or should we identify specific cannabinoids in certain amounts when they seem to be abused as street drugs? Any form of THC is at least suspect as an intoxicant and so that is a start, but there could very well be other intoxicants we don’t know about yet. Much like the serving sizes, we were more interested in presenting a framework, and then calling on stakeholders to have that discussion.”

It must be said, though, that if it is so difficult to define intoxication, it’s kind of a hard sell to pass the buck on the issue over to Congress. Who has more experience in this issue, Congress or the members of ATACH? It seems like a missed opportunity to truly inform or influence the process, even if all you have is the skeleton of a workable definition.

Dosage Information Should Be Standardized

The paper points out that it can be difficult for consumers to anticipate what a dose of an intoxicating hemp product will do, since the potency of different isomers can differ substantially. They write, “it is essential that hemp-synthesized intoxicants also have serving sizes that are uniform and enable consumers to anticipate the potency of the product.”

They propose two methods of doing this:

- Total Intoxicating Cannabinoid Content (TICC): This is under development by ASTM International (with help from ATACH), and aims to establish a standard for the “intoxication level” of a cannabinoid. It will initially focus on delta-9 THC, and this will then be used as a basis for grading the relative intoxication level of other cannabinoids. According to the ATACH paper, this would represent “the aggregate concentration of intoxicating cannabinoids in a serving,” and ASTM also compares it to alcohol’s ABV measurement. These both imply that this would be a percentage amount, based on delta-9’s potency.

- Delta-9 Equivalency (DNE): ATACH proposes a system they call “delta-9 equivalency,” in which they would use delta-9 THC as a reference point, and essentially “translate” a dose of another cannabinoid into the equivalent dose of delta-9 THC. The DNE doses could then be combined in a manner similar to the TICC approach.

These two methods overlap, both proposing using delta-9 THC as a standard by which to convey the potency of other cannabinoids. In theory, this is an excellent idea. In practice, ATACH notes that it is not likely to be useful for the 2023 Farm Bill, because the scientific knowledge to institute it is simply not available:

“this framework requires significant investigation and real-world validation from researchers and consumers to ensure its reliability, and will likely take time to develop.”

We asked ATACH about this issue, given that regulators can’t just wait for this system to be feasible, and they pointed out that:

“Some of the researchers are very concerned that we were talking about a regulatory system before products are fully understood – but there needs to be a place to establish consumer protection safeguards. In a perfect world, all of the science would be done and we would know everything before a new intoxicants industry takes off, but we do feel we are at an inflection point where something can be done now. It’s clear that we don’t have the option to wait.”

They’re right: we really don’t have the option to wait. All in all, it seems that regulators should use a simpler approach (e.g. simply listing the amounts of each intoxicating cannabinoid and summing the total dose) rather than attempt to do something based on evidence which we don’t have.

Impose a Milligram Serving Limit on Hemp Products

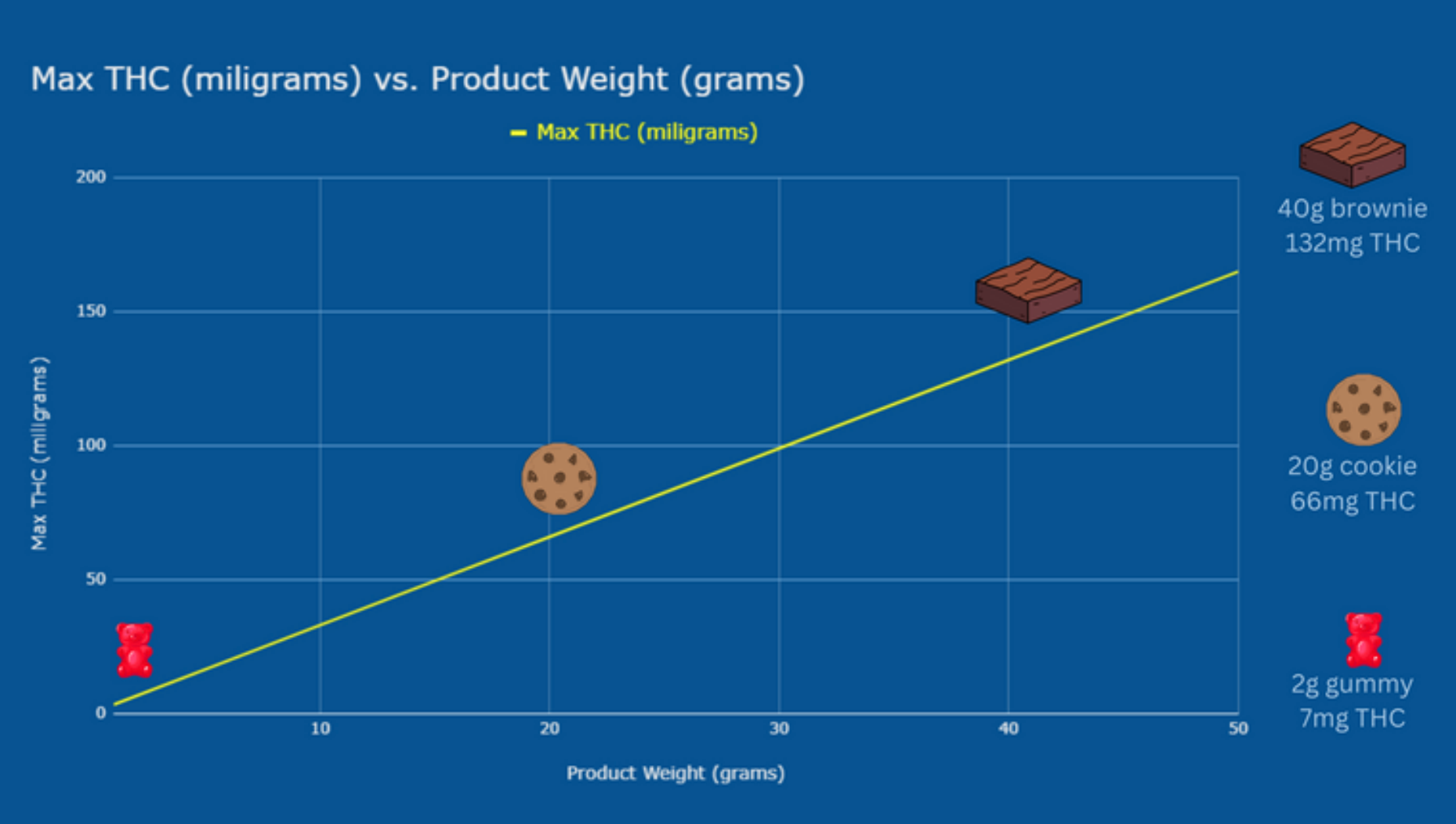

The paper points out the many problems with using a simple concentration of delta-9 THC as a measure of legality for products. In particular, a graph from ATACH (PDF page 17/document page 18), plots a straight line illustrating how the allowed dosage of THC varies with the total dry weight of the product.

For example, a 2 g gummy could have 6 mg of THC, if we assume the dry weight is the total weight (in practice, the dry weight and consequently the allowed THC dose would be lower). At the other end of the scale, a 40 g brownie could have a huge 120 mg of THC and still be within the limit (again, the actual “dry weight” figures would be lower). This would never be allowed in a single serving under a regulated marijuana program.

This is why the paper proposes that the new definition of hemp “should include serving sizes for package limits of THC in milligrams, in addition to dry weight percentages for raw plant material.”

Unfortunately, the paper offers no solid recommendations as to what this dose should be. ATACH commented to us that:

“There is no answer that will satisfy everyone, and states are not consistent. But the thinking behind a serving size and a per package limit amounts is to create a delineation between non-intoxicating and intoxicating (adult-use) products. Our policy suggestions go about this by creating a Delta-9 equivalent which is probably most analogous to an ABV (alcohol/volume) that a consumer would reasonably understand how a product is likely to impact them.”

While standardizing the dosage information shown to the consumer would help in a way, this just moves the issue: what would the mg limit be in the new system? If no answer will satisfy everyone, can this be the basis of policy? And if we really do have to make a call anyway, who should we upset?

Increasing the On-Farm THC Limit for Plant Material

The paper points out that many farmers lose entire crops if they test “hot” at some point in the growing process, and that this represents an undue burden on them. They suggest raising the threshold for hemp plant material to 1% on a dry weight basis.

This will undoubtedly make the prospect of hemp farming more appealing and would prevent farmers from losing revenue through accidentally – and ultimately temporarily – exceeding the strict 0.3% THC limit. ATACH argues that, “hemp varieties used for CBD production can cross the 0.3% THC threshold per harvest, even when well short of the amount needed to lead to intoxication.”

Adding, “As we now know, the real intoxicant production from hemp plant stock begins in a laboratory and well after farming is complete, which is not currently limited in any significant way.”

This isn’t necessarily the case, though. As the paper showed in the last section, something meeting the 0.3% threshold can easily produce an intoxicating product, and if this level couldn’t be reached on the farm, there’d be no need to increase the threshold in the first place.

Mandate Testing of HSIs and Standardize the Process of Production

The paper points out that only very few states require testing of hemp products prior to sale, and that even when it is required, it may not be reliable because “the processes used may not be sufficient to guarantee consumer safety due to the presence of unknown chemicals in these products.”

Part of this issue comes down to the lack of standardization of the production of HSIs, which means that different manufacturers use different chemicals and so would have different contaminants in their products. Without standardizing this process, testing protocols would have to be much broader than they currently are to truly capture the possible chemical content of the products.

The paper calls on manufacturing processes to be standardized, and for federal and state regulators to “work together to develop a system for identifying harmful chemical residues and other contaminants that can be applied uniformly across all jurisdictions that allow regulated access.”

Only Adults Should Buy Intoxicating Hemp Products

This doesn’t need much explanation: just like regulated cannabis markets limit sales to adults aged 21 or over, intoxicating hemp products should only be available to adults.

What the Paper Could Do Better

As with any paper, piece of research or article, there are places where this white paper misses the mark and doesn’t present its case as effectively as it could.

- Lack of specificity: The paper proposes a “reasonable” limit in milligrams for HSIs, but does not propose what that limit should actually be, and most answers are problematic in some way. If we limit it to 5 mg per serving, this will still be intoxicating to the level of edibles in some legal states. If we make it more restrictive, the serving size would give no useful safety information for people who are looking to get high. Stopping ridiculously high single-serving doses is sensible, but as soon as you propose a specific number things don’t seem so simple.

- Proposals that aren’t currently workable: Delta-9 equivalency is a good idea, as ASTM and ATACH both propose in some way. However, we simply do not know enough about the relative potency of different rare cannabinoids to put this system into practice. ATACH also points this out, and the figures given in the table are footnoted as just “illustrative.” For the next Farm Bill, coming this year, regulators need an approach that can work now.

- Muddy definitions: Delta-9 THC, arguably the most well-known natural cannabinoid, is classed as a “hemp synthesized intoxicant” by the paper. In the context of the hemp delta-9 industry, this is basically true, but the “basically” is doing a lot of heavy lifting there. In fact, while most products in our lab study did use THC converted from CBD, around 18% used naturally-sourced hemp delta-9 and another quarter used delta-9 naturally produced by cannabis. So is delta-9 THC really a synthesized intoxicant in these cases? Is it one overall? It is not clear.

- Is the industry really so bad? The paper presents HSIs as if they present an unknown risk, particularly in the context of manufacturers using varying processes and that they “often do not” remove dangerous components before products are put on sale. This is only presented with vague assertions. In fact, heptane is used as an example of such a problematic component, but a cursory online search shows that products are tested for heptane by reputable manufacturers. How common is this problem? Should ordinary consumers be worried? Unfortunately this is left vague, underpinning the notion that “something must be done.”

Conclusion: Congress Must Act on Hemp Intoxicants, But How?

As the paper argues, cannabis should be legalized across the country. Would people really be so interested in a questionable delta-8 gummy when they could head to a licensed dispensary and pick up a tested, normalized and consistent product? Unfortunately, the 2023 Farm Bill is coming before this is likely to happen, so Congress must pay attention to the recommendations made by this paper, if it stands any chance of closing the loopholes it created back in 2018.

The open question, unfortunately, is how exactly all of this should work. We, like the paper, may hope that we can just leave it to lawmakers and they’ll work it out on their own. But lawmakers enrolling statutes without thinking them through properly is what got us into this situation in the first place.

Maybe they’ll get it right this time, maybe they won’t.